Proc Nutr Soc. 2023 Nov 29:1-24. doi: 10.1017/S0029665123004858. Online ahead of print.

NO ABSTRACT

PMID:38018402 | DOI:10.1017/S0029665123004858

Waste Manag. 2023 Dec 19;175:12-21. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2023.12.010. Online ahead of print.

ABSTRACT

Food waste contributes significantly to greenhouse emissions and represents a substantial portion of overall waste within hospital facilities. Furthermore, uneaten food leads to a diminished nutritional intake for patients, that typically are vulnerable and ill. Therefore, this study developed mathematical models for constructing patient meals in a 1000-bed hospital located in Florida. The objective is to minimize food waste and meal-building costs while ensuring that the prepared meals meet the required nutrients and caloric content for patients. To accomplish these objectives, four mixed-integer programming models were employed, incorporating binary and continuous variables. The first model establishes a baseline for how the system currently works. This model generates the meals without minimizing waste or cost. The second model minimizes food waste, reducing waste up to 22.53 % compared to the baseline. The third model focuses on minimizing meal-building costs and achieves a substantial reduction of 37 %. Finally, a multi-objective optimization model was employed to simultaneously reduce both food waste and cost, resulting in reductions of 19.70 % in food waste and 32.66 % in meal-building costs. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of multi-objective optimization in reducing waste and costs within large-scale food service operations.

PMID:38118300 | DOI:10.1016/j.wasman.2023.12.010

UW Health's culinary services department has about 300 full-time employees. | Photo courtesy of UW Health

The culinary team at University of Wisconsin Health (UW Health) wants to change the stigma around hospital food.

“Food within a healthcare system is not known to be necessarily delicious or craveable, something that you would really seek out," said Amy Mihm, clinical nutrition specialist at UW Health. "And we wanted to change that model.”

The hospital system takes a holistic approach to foodservice and aims make its cafeterias a welcoming place for diners.

“For years, we've talked about having the healthy choice be the easy choice and the best price choice," said Lisa Bote, manager of culinary services. "We want to make the operation a place where our customers want to come and eat.”

The team works across two departments—culinary services and clinical nutrition services, serving three hospitals in UW Health’s system. Culinary services works in two production kitchens, powered by about 300 full-time employees, while clinical nutrition serves inpatient and outpatient adults and pediatrics.

In addition, UW Health has a milk and formula lab on site and a learning kitchen at one of its hospitals.

“So, we really have a unique, I think, situation where we have the full lifecycle,” said Megan Waltz, director of culinary services and clinical nutrition services.

Feeding a diverse population

The system prides itself on serving a varied menu to account for the diversity in the population it serves.

In 2023, UW Health received its third Practice Greenhealth Circles of Excellence award, which evaluates how healthcare systems are promoting and growing their sustainable food systems. Lawson said one of the areas the team was recognized for was serving foods that represent its staff’s cultures.

“We rely a lot on our own staff, because of the diversity of the staff, to really bring ideas to us about things that would be great options to add,” said Waltz.

Last year, UW Health also won a recipe contest put on by nonprofit Health Care Without Harm. When looking at which recipes to submit, the team hoped to tell the stories of its staff and its diverse customer base.

It decided to submit a recipe the team developed in 2021, an Afghan-inspired vegetable korma.

When the Taliban took over Afghanistan, Wisconsin saw an influx of Afghan refugees, Bote said, and UW Health’s children’s hospital received many pediatric patients from Afghanistan. They heard feedback from these patients and their families that the offerings on the menu didn’t resonate with them. The team quickly jumped to action, consulting a staff member who had emigrated from Afghanistan in her teens.

The vegetable korma | Photo courtesy of Health Care Without Harm

The vegetable korma | Photo courtesy of Health Care Without Harm

“And she came up with this vegetable korma dish,” Bote said. “And it's savory, it's delicious. It's filling, it's comforting. It was a dish that her mother taught her how to make.”

Defining sustainability

When it comes to sustainability, UW Health considers more than just the environment. Lawson said the team also looks at community health and efforts to support local partnerships. She said that work in that area started about 10 years ago, when rates of pediatric obesity began to rise.

In response, the team began to develop nutrition and sustainability standards. “And we did that because our vision was that the food that we serve within our healthcare system should really model the behaviors that we're asking people to do on their health and wellness journey,” said Waltz.

One of UW Health’s big sustainability efforts is its push towards plant-forward fare. The health system signed onto the World Resources Institute’s Cool Food Pledge in 2019, setting a goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 25% by 2030. Mihm said that the Cool Food commitment sparked an opportunity for the team to evaluate how it sources food and develops menus.

The team focuses its plant-forward strategy on produce, rather than meat analogues, and markets the food in a way that highlights what is being added to the plate, rather than what’s being taken away.

“I think when you speak plant forward, for some individuals that can be intimidating,” said Mihm. “So how do you develop an approachable menu? Approachable types of foods that may or may not be familiar to somebody, but yet, because it tastes amazing, they're willing to give it a try.”

A Mediterranean grain bowl. | Photo courtesy of UW Health

A Mediterranean grain bowl. | Photo courtesy of UW Health

Waltz said that word choice surrounding plant-centric options is also important. Rather than use terms like vegetarian or vegan, they opt to describe menu options as plant-forward.

In addition, Bote noted that the team has worked on yield studies to look at ways to reduce meat in some dishes and add more vegetables, beans or pulses.

“When we do this, we don't necessarily make a large announcement and do marketing around it for our customers,” Bote said. “But we hold that behind the scenes, and we hear the customers’ feedback about any changes that we've made. And typically, there's good feedback about it because the food simply tastes good.”

One way the team markets its plant-forward fare is through sampling events. Bote said that sometimes diners are a bit apprehensive about new menu items, but they’re still willing to try and are often surprised at the flavors.

Customer feedback to plant-forward items has generally been positive, and the majority of recipe requests the team receives are for plant-forward options. Culinary services also goes through quite a bit of tofu, as one popular recipe is tofu based.

The team agreed that while diners have gotten on board with the plant-forward movement, it has taken some time.

“When we began this journey, literally 10 or more years ago, we may have received more negative feedback about how the food system was changing,” said Mihm.

Waltz attributes the change in customer perception in part to COVID. She said she has seen a larger focus on personal health in recent years, adding that she saw a pretty high increase in the number of UW patients with pre-diabetes during the pandemic.

“So, knowing that people were starting to see that as disease rates were going up for chronic conditions, we also started to see people paying more attention to their health and wellness, and what resources they need,” said Waltz.

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct the name Megan Lawson to Megan Waltz.

Pour lutter contre le gaspillage alimentaire, le CHU de Nantes donne les repas qu'il produit en trop à une association locale depuis août 2021. Un dernier partenariat a été noué ce jeudi 23 août entre son site de Laennec et l'antenne locale du Secours populaire. En tout, une centaine de repas par jour seront désormais redistribués à des personnes précaires.

Chaque jour, les services de restauration des hôpitaux français produisent un peu trop de repas par rapport à la consommation des patients.

"Nous produisons nos repas par anticipation, un à trois jours à l'avance, en nous basant sur les historiques de consommation. Mais c'est impossible de savoir à l'avance combien de patients nous aurons à nourrir précisément."

Martial CoupryIngénieur Restauration du CHU de Nantes

Sur 12 000 repas produits, le CHU en produit en moyenne une centaine en trop par jour.

/regions/2023/08/23/64e613f2b9421_cuisine-centrale-hsj-18.jpg)

Alors depuis août 2021, le centre hospitalier a noué un partenariat avec Tinhi Kmou, une association qui lutte contre le gaspillage alimentaire.

"On récupère les repas dans les services de restauration des sites de l'Hôtel-Dieu et de Saint-Jacques et à 15h, on les dépose dans notre frigo libre-service, juste à côté du local de l'association."

Alain TahaPrésident de l'association Tinhi Kmou

En tout, 25 000 repas sont récupérés chaque année par les bénévoles de l'association. Cette dernière fournit une aide alimentaire à 100 à 150 personnes par jour grâce à ces dons, mais aussi grâce aux glanages réalisés sur les marchés.

À lire aussi : Nantes : la solidarité pose ses étals sur le marché de Bellevue et ça dépote !

Désormais, c'est au tour du site de Laennec de se séparer de ses 30 à 40 repas en surplus. Une petite partie sera récupérée deux à trois fois par semaine, par les bénévoles du Secours Populaire de Saint-Herblain.

"C'est une des actions qui nous permettent de compenser la baisse des ramasses dans les grandes surfaces. On a perdu 2/3 des dons en quelques années."

André LamyResponsable de la logistique et des approvisionnements alimentaires au Secours populaire de Saint-Herblain

La faute aux rayons anti-gaspillage qui fleurissent dans les grandes surfaces. "Tout ce qui part en panier à 1 € ou 3 €, c'est tout ce que les associations n'auront plus."

À lire aussi : Loi anti-gaspillage : les grandes surfaces à l’heure de la solidarité forcée

"Nous allons dorénavant devoir nous organiser, car il faudra être en capacité de redistribuer ces repas dès le lendemain à cause des dates de péremption limitées. Mais il n'y a pas de petits dons, à nous d'être réactifs !"

Du côté du CHU, on se félicite d'avoir désormais trouvé un débouché pour la totalité des surplus produit par les services de restauration.

J Hum Nutr Diet. 2023 Aug 10. doi: 10.1111/jhn.13227. Online ahead of print.

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Dietitians (RDs) are well-positioned to promote sustainable food systems and diets. This research aims to review the literature for how RDs in Canada define sustainability and determine the types of relevant activities that exist in practice as described in published literature.

METHODOLOGY: Using standardized scoping review methods, researchers searched CINAHL, ACASP, PubMed, and ENVCOM databases to identify peer-reviewed articles and conducted a grey literature search to locate other publications related to sustainability in Canadian dietetic practice. Qualitative, thematic coding methods were used to examine definitions and existing practice. The PRISMA extension for scoping reviews guided reporting.

RESULTS: The search resulted in 1059 documents, and after screening, 11 peer-reviewed and 16 grey literature documents remained. Ten unique definitions were used, the most common being Sustainable Diets. Definitions were multidimensional, including environmental, social, economic, and health dimensions, and 31 unique sub-topics. However, existing practice activities appear to reduce actions to 1-2 dimensions. Existing practice areas well-reflected include Food and Nutrition Expertise, Management and Leadership, Food Provision and Population Health Promotion. Notable gaps include action in Professionalism and Ethics and Nutrition Care.

CONCLUSIONS: No one definition supports all professional contexts, and agency in choice of language to define the work is helpful for contextual clarity. Strengthening practitioners' ability to analyze issues using systems thinking and applying this in practice will help to address challenges and reduce risks of trade-offs. Updates to competency standards that reflect the breadth of existing activities, as well as curricular supports or practice standards, are needed. This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved.

PMID:37565587 | DOI:10.1111/jhn.13227

L'une des solutions de plus en plus évoquées pour baisser radicalement les émissions de gaz a effet de serre en France d'ici 2030 est de modifier notre alimentation, en particulier la viande rouge, qui pèse lourd sur les émissions de l'agriculture. A Marseille, les hôpitaux ont donc décidé de diviser par deux la quantité servie aux patients.

Publié le 18/07/2023 17:08

Temps de lecture : 2 min.

Comment réduire nos émissions de gaz à effet de serre d'ici 2030, comme le souhaite le gouvernement ? L'un des leviers possible est celui de l'alimentation, et en particulier l'élevage bovin. À cette fin, la Cour des comptes recommande d'ailleurs de réduire la taille du cheptel français.

À Marseille, les hôpitaux ont décidé de réduire par deux les quantités de viande rouge servie à ses patients. Le docteur Guillaume Fond a accompagné sur cette voie l'AP-HM, les hôpitaux de Marseille. Selon lui, "on a tout à gagner à faire cette transition, et le plus vite possible. Il y a une urgence, le GIEC nous le rappelle", soutient le psychiatre.

"Il faut remplacer de la viande de mauvaise qualité - puisque le budget à l'hôpital est restreint - qui plus est conditionnée en barquette - et à l'inverse, on va vraiment augmenter les produits locaux et de saison".

Docteur Guillaume Fondà franceinfo

Le psychiatre estime qu'à "budget constant," l'AP-HM va pouvoir "fournir une alimentation de meilleure qualité, qui sera aussi meilleure pour la santé de nos patients".

Les hôpitaux de Marseille ont donc tranché dans la viande rouge, qui ne sera plus aussi présente sur les plateaux-repas de ses patients. Désormais, un menu végétarien est proposé pour le dîner, avec "des pois chiches, des haricots blancs, des lentilles, qui apportent de bonnes protéines végétales, mais aussi des fibres qui vont nourrir le microbiote, et des glucides complexes qui vont apporter une bonne énergie", explique le docteur Guillaume Fond, qui assure qu'après enquête auprès des patients, "ils préfèrent le végétarien le soir". Il existe toutefois des dérogations pour les personnes les plus fragiles.

Sur ce sujet, Marseille est à l'avant-garde : l'idée de départ était de supprimer totalement la viande rouge dans les hôpitaux de la Ville, mais finalement, en divisant par deux la quantité servie, l'AP-HM va s'aligner sur les recommandations des autorités sanitaires. Cette nouveauté est vécue comme une petite révolution culturelle, et il a fallu lever pas mal de freins. "Il faut avancer doucement parce que l'alimentation à l'hôpital est un sujet complexe, reconnaît Caroline Bouchareu, directrice de la transition écologique. Il faut prendre le temps d'expliquer, que ce soit aux équipes avec lesquelles on travaille, mais aussi aux patients", poursuit la responsable.

J Hum Nutr Diet. 2023 Jul 25. doi: 10.1111/jhn.13211. Online ahead of print.

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Allied health professionals (AHPs) have an important role to support the Greener National Health Service (NHS) agenda. Dietitians are AHPs who are already demonstrating strong influence on food sustainability advocacy. There is call for more collaboration across the health professions to optimise "green" leadership in the pursuit of planetary health. The present study aimed to investigate the perceived role of AHP leaders and future leaders around more sustainable healthcare practices.

METHODS: A mixed methods approach using audio-recorded semi-structured interviews with strategic AHP leaders (n = 11) and focus groups with student AHPs (n = 2). Standardised open-ended questions considered concepts of (i) leadership, (ii) green agenda, (iii) collaboration and (iv) sustainability. Purposive sampling used already established AHP networks. Thematic analysis systematically generated codes and themes with dietetic narratives drawn out specifically as exemplars.

RESULTS: The findings represent diverse AHP voices, with six of 14 AHPs analysed, including dietetic (future) leaders. Three key themes emerged: (1) collective vision of sustainable practice; (2) empowering, enabling and embedding; and (3) embracing collaborative change. Dietetic specific narratives included food waste, NHS food supply chain issues, and tensions between health and sustainability advice.

CONCLUSIONS: The present study shows that collaborative leadership is a core aspiration across AHP leaders and future leaders to inform the green agenda. Despite inherent challenges, participant perceptions illustrate how "change leadership" might be realised to support the net zero agenda within health and social care. Dietitians possess the relevant skills and competencies, and therefore have a fundamental role in evolving collaborative leadership and directing transformational change towards greener healthcare practices. Recommendations are made for future leaders to embrace this agenda to meet the ambitious net zero targets.

PMID:37489277 | DOI:10.1111/jhn.13211

St. Joseph's Health Care London is calling out for local farmers and food growers who can supply fresh and locally sourced produce for its inpatients and residents.

The London, Ont., hospital is hoping to hear from farmers about their business and capabilities to determine what local growers can provide through a request for information (RFI) that will help structure a deal that would benefit the whole community.

It's the first step to figuring out a long-term plan that will eventually pave out details that include, but aren't limited to, the products that can be grown and how to manage orders and deliveries.

"We're looking to build a connection with our local producers and farmers to try and be able to get more of our produce from those who are right around us in the community," said Lindsay Botnick, director of food and nutrition services (FNS) at St. Joseph's.

"By doing it this way, we're doing our best to reach some of those growers and farmers that maybe haven't always had that connection with hospitals but are just down the road from us."

The initiative is part of the national Nourish Project, which includes St. Joseph's FNS team and six other organizations across the country. It seeks to improve the environment through reducing waste, buying local, and better food sustainability practices.

"We're always trying to nourish our patients and making sure they have the variety of food and vegetables because food is healing," Botnick said. "There's a difference in taste when you get something locally [grown], so we're trying to have that quality as best as we can."

Botnick said the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of having reliable connections close to home as the community reinvests in itself.

The method allows farmers to offer their insights on how to best meet the community's needs, said Toby O'Hara, general manager of Healthcare Materials Management Services (HMMS).

HMMS is a joint venture between St. Joseph's and the London Health Sciences Centre which oversees functions of its contracts and inventory.

"The worst thing we can do is create a contract based on what we think we want and it excludes the capabilities of our local growers, so the approach we're taking on this one is being open minded and asking them about their operations," said O'Hara.

O'Hara noted that in the past, the hospital would work with a food distribution company, who would offload mostly frozen food or pre-packaged food, with some local fresh produce.

"The way we've always done things hasn't necessarily resulted in the best outcomes and this really focuses on the local economy and health needs of patients," he said.

The RFI is available through the Ontario Tenders Portal until Sept. 1. Potential suppliers are invited to ask any questions about what the hospital is looking for, how they can respond, and any other inquiries they may have.

Once questions are submitted, HMMS will answer it in a singular format that everyone who is involved can see in August, after which it will take the information and work with St. Joseph's to create a contract later this year.

Questions can be directed to [email protected] or 519-453-7888 ext. 62300.

A table outside a Boston hospital cafeteria offers samples of a daily special: a soba noodle stir-fry with shiitake mushrooms and mixed vegetables. Andrea Venable, in her bright red uniform shirt, picks up a small plastic cup and peeks inside.

“Looks like noodles,” says Venable. She shrugs. “I don’t know. I guess I’ll give it a try.”

Venable works for parking services here at Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital. She’s noticed the hospital cafeteria introducing more plant-based dishes to taste — dishes that become regular features on the menu.

“I think it’s good for the people that eat, like, vegetarian,” she says.

Venable is not one of them. She likes meat and isn't interested in eating less of it.

Therein lies the challenge for Faulkner Hospital leaders. It's hard to persuade people to cut back on meat. The Faulkner started trying about 20 years ago for health reasons. "Meatless Mondays" generated a lot of complaints at the hospital. And don't even ask about the time they cut fries and chicken nuggets from the menu.

But hospital leaders say they've noticed a shift since they began framing their efforts around climate change. Patients and employees who wouldn’t adjust their diet to improve their own health are doing it for the greater good.

“It’s a little bit more altruistic in that way,” says Susan Langill, the hospital’s director of food services, which are provided by the company Sodexo. “They are putting the earth and future generations before their own health.”

Faulkner is one of seven Massachusetts hospitals and universities that have signed an international pledge to reduce food-related greenhouse gas emissions 25% by 2030. The hospital is starting with the cafeteria and will expand to changing patient meals, too.

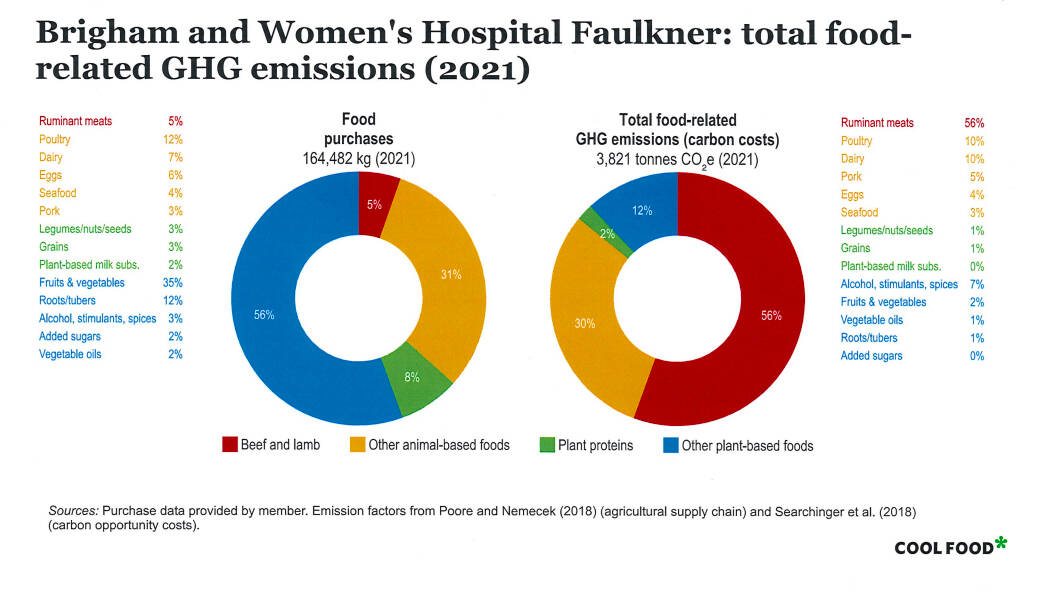

A key factor, possibly the key, will be serving less meat. The latest hospital data shows beef and the occasional order of lamb make up just 5% of food purchased by the Faulkner, but represent 56% of the hospital’s food-related greenhouse gas emissions.

"Seeing that graph," says Langill, "was the game-changer for me.

But Langill says many diners still need a nudge. The Faulkner’s strategies, focused first on hospital staff, are subtle, even a bit … stealth. Here’s one:

“Celebrate what’s in the dish as opposed to what’s been taken out of it,” Langill says.

The strategy originates from a playbook of suggestions that comes with the climate emissions pledge.

Today’s soba noodle special, for example, is meat-free. But elegant, descriptive signs on the tasting table don’t say that. In fact the words vegan or vegetarian don’t appear in the name of any dishes on the hospital cafeteria menu. The hospital has learned that dishes labeled vegan pretty much only attract, well, vegans.

“Lots of folks don’t identify as vegan or vegetarian,” Langill says. “So instead we’re marketing dishes based on the flavor or cultural benefits and celebrations of that food.”

Plant-based or plant-rich foods might be at the front of the buffet line. There’s often a meat-free option like eggplant parm next to chicken parm as a ready alternative. Contests are popular, such as asking staff to try a different plant-based item from the menu every day for 30 days. The cafeteria staff offer cooking demonstrations with tofu and tempeh, and hand out recipe cards.

Dr. Len Lilly, a cardiologist who stops to grab a soba noodle sample, is pleased. Climate-friendly foods are healthier as well.

“There have been times I’ve come to this cafeteria and the choices have been between steak and hamburger,” says Lilly. “That’s not good.”

Other hospital staff are on board with the gradual changes, too.

Matt Wilson, an operating room nurse, and his wife have started eating vegan once a week for dinner. They’re getting used to friends’ jokes.

“They always laugh at me when I tell them I eat vegan meals, but that’s OK,” says Wilson in between bites of soba noodles. “They’ll convert. I got faith.”

Because, says Wilson, there are some big benefits.

“The greatest thing about vegan meals is they could be huge plates but you never feel that full,” he says. “So, it doesn’t make you too groggy” in the operating room.

The next frontier for the Faulkner and its larger affiliate Brigham and Women’s Hospital is new patient menus. They will have more plant-based dishes where adding meat is an option, like tacos or a barbeque burger with a choice of patties: black bean, turkey, chicken or beef.

The hospital is already nudging patients with daily meat-free specials: a roasted edamame salad or a teriyaki tofu and grilled pineapple wrap, for example.

Food is likely a small part of most hospitals' greenhouse gas emissions, but advocates say it's a critical step in reducing emissions. And Health Care Without Harm, a group that helps the industry address climate change, says it's one that will have an impact.

The climate pledge includes using more sustainable foods such as those highlighted by the World Wildlife Fund’s Future 50 Foods list. It includes fava beans, buckwheat and okra, foods that could help diversify our farming and shift dependance away from corn, rice and wheat. The goal is to expand the range of beans, grains and vegetables commonly eaten to preserve biodiversity and help farmers deal with the impacts of climate change.

Meatballs made with textured soy protein for zucchini pasta and meatballs with roasted tomato and shallot coulis. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)

Meatballs made with textured soy protein for zucchini pasta and meatballs with roasted tomato and shallot coulis. (Jesse Costa/WBUR)The Faulkner’s general manager for food services, Mike Hanley, says he adds something from the list to specials regularly. And the hospital serves local fish twice a week, often not the typical fare. Diners may see species like dogfish, cusk, bluefish, skate and monkfish.

“Anything that swims in our waters,” says Mike Hanley, general manager for food services at Faulkner Hospital. “You name it, we’ve served it. And it’s cheaper than beef.”

Some 60 hospitals, universities, major corporations and cities have signed the pledge to cut food-related greenhouse gas emissions. The project, led by the World Resources Institute, measures progress in two ways: emissions linked to the weight of food purchased, where the goal is a 25% cut, and emissions per calorie which need to drop 38%. Buying fewer pounds of beef as compared to food from plants is the fastest route.

The science of calculating emissions for individual foods is new, so estimates are rough. They’re based on the type of food, the amount of land used, the agricultural supply chain and other factors.

As of 2021, the first 30 organizations to sign on cut food-related emissions per calorie by 21%.

“We hope we’re showing that change is possible,” says Richard Waite, senior research associate in food and climate programs at the World Resources Institute. “But we need many others to be making these same types of changes if we want to, as a world, get to where we need to be by 2030.”

Boston Medical Center was among the first to join and is roughly half-way to the overall 25% reduction in emissions goal. Another early signer, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, created a forecasting tool that helps the kitchen staff see the relationship between emissions and food purchases to help them design menus.

One year into the pledge, Faulkner is showing a 2.2% decrease in emissions per calorie. The Brigham has cut emissions per calorie by 20%.

Langill says she’s optimistic that both hospitals will hit the target.

“As long as we continue to do things like this,” she says, waving toward the tasting table, “and convince people to change their habits.”

On cue, Andrea Venable, the enthusiastic meat eater, strolls past the tasting table, again.

“I gotta say it’s good,” she says, picking up another sample, “really good.”

Each year, hospitals across the United States dish up billions of meals. Those responsible for feeding thousands of visitors, patients, and employees every day contemplate numerous issues, from nutrition requirements to skyrocketing expenses.

But increasingly, they also focus on another significant concern: the environmental impact of what they serve and how.

That makes sense given the role that food plays in helping or harming the planet. For example, 34% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions worldwide are food-related, according to a 2021 Nature Food article. What’s more, health care has a significant environmental footprint: If the global health care sector were a country, it would be the fifth-largest contributor to GHGs. And a large chunk of hospitals’ environmental impact comes from their food services.

This reality worries health care leaders who want to avoid contributing to environmental problems that can cause or worsen health conditions for the patients and communities they want to protect.

“You just can’t have healthy people on a sick planet,” says John Stoddard, associate director for climate and food strategy at the environmental nonprofit Health Care Without Harm (HCWH). That organization collaborates with nearly 2,000 U.S. hospitals and health systems working on the connection between food and sustainability.

Stoddard notes growing interest in the issue. “About 10 years ago, it was a really hard sell. I would cold-call people to try to convince them, and they didn’t see the connection between food and the environment. Now, they come to me asking what they should do.”

Currently, 81 hospitals have signed the Cool Food Pledge, which aims for a 25% reduction in food-related emissions by 2030. That’s up from 4 hospitals in 2018, when HCWH and other organizations first launched the initiative.

“About 10 years ago, [people] didn’t see the connection between food and the environment. Now, they come to me asking what they should do.”

John Stoddard

Health Care Without Harm

Hospital leaders are approaching the issue from numerous angles, including how their food is produced, transported, prepared, packaged, and discarded. Often, they focus on three key areas: swapping plant-based food for meat, buying locally and responsibly, and discarding waste in more environmentally responsible ways.

“We look at how we can reduce the environmental impact from food at every decision point,” says Diane Imrie, RD, MBA, who oversees the production of 2 million meals annually as director of nutrition at the University of Vermont Medical Center (UVMMC) in Burlington. “This adds up to a big enough effect on the environment that if we were ignoring it, we would feel we were not living up to our commitments to our patients and to the planet.”

The power of plants

Growing plant-based foods (like beans and vegetables) uses less land and water than animal-based options (like meat, poultry, and dairy). It also produces far fewer GHGs. In fact, halving U.S. meat consumption would be tantamount to taking 47.5 million cars off the road, a University of Michigan study estimates.

The number of hospitals working to trim their meat offerings is growing. More than 80% of reporting hospitals in the HCWH network were doing so in 2022, up from 57% in 2017, says Stoddard. Boston Medical Center (BMC) has reduced its beef purchasing by 22% over the past few years, according to Senior Director of Services David Maffeo, and at UCLA Health plant sources of protein now make up more than a third of all protein purchases.

Leaders can turn to some sophisticated tools as they do this work. “We can use a Practice Greenhealth GHG calculator to compare the impact of using 400 pounds of chicken versus 400 pounds of beans,” says Lisa Boté, manager of culinary services for UW Health, which has three hospitals in the Madison region of Wisconsin. “We can even look at the change in GHG emissions if we take out a slice of cheese from a sandwich.”

But making such changes palatable to patients and cafeteria customers isn’t always easy.

“Food is near and dear to people’s hearts. If you start messing around with their options, it can be tough,” says Kyle Tafuri, vice president for sustainability at Hackensack Meridian Health, which has reduced meat-related GHGs at its 18 New Jersey hospitals by 39% in recent years.

Hackensack culinary staff worked to develop some mouth-watering options. For example, beet greens don’t simply get chopped and boiled; they instead appear in a salad with candied walnuts and a citrus dressing. Other hospitals try small steps, like swapping a 100% beef burger for a version that’s 70% beef and 30% mushroom.

At UW Health, those involved thought hard about how to pitch menu changes. “We are Wisconsin. Beef is a staple,” says Megan Waltz, MS, RD, director of culinary services and clinical nutrition. “People may think, ‘Don’t take away my red meat,’ so just encouraging eating more plants can be more acceptable and less shaming.” In addition, staff helped ease cafeteria visitors into plant-based foods by offering free samples of unfamiliar items like garbanzo bean salad and vegetable korma.

When it comes to the animal products they do serve, hospitals are also working to go antibiotic-free. “In this country, more antibiotics are used in meat than in people,” and pervasive use of antibiotics in animals can increase dangerous resistance among humans, says Tafuri.

Antibiotic-free options are more pricey, but serving less meat overall helps — as do other cost-cutting steps. “We’ve worked hard with the team, from the administration down to frontline cooks, to find ways to be responsible financially and environmentally,” Tafuri says. “It can be done.”

Buying locally — and responsibly

In the United States, food often travels thousands of miles from farm to plate, with environmental impacts all along the way.

Imrie still remembers learning about the trajectory of fish she had been buying from Alaska. “It was being flown to China, packaged, frozen, and then shipped back. That was pretty ridiculous,” she says.

But Imrie and others are buying closer to home not just to reduce their “food miles,” but also to encourage local farmers to pursue more environmentally friendly practices.

At UW Health, that means taking into consideration whether certain producers are adopting organic and other environmentally responsible farming techniques. At UVMMC, it means providing local partners with a more robust seed base, one that boosts water absorption and habitats for pollinators.

At BMC, much of the produce served is hyper-local: grown right on top of one of the hospital’s buildings. The 2,658-square-foot farm, launched in 2017, yields about 5,600 pounds of fruit and vegetables each year.

The roof farm offers many environmental upsides besides zero food miles. Plants ingest carbon dioxide and other pollutants, says Maffeo, and they cut energy use by serving as an extra layer of insulation. They also absorb rainwater, which prevents storm drains and rivers from being flooded by runoff.

Now, BMC is getting ready to expand its agricultural efforts with a new farm on a second building. Scheduled to open this summer, the new spot will yield twice as much produce.

Waste, not!

Food-related refuse accounts for 10% to 15% of all hospital waste produced each year. Just one hospital kitchen alone can churn out hundreds of tons of food waste annually.

That’s worrisome, environmental leaders say, in part because discarded food unleashes dangerous GHGs as it decays. In fact, cutting U.S. food waste in half would reduce GHGs by the same amount as shuttering 23 coal-fired power plants.

Some hospitals are working to curtail food waste before it happens. Doing so often involves methodically measuring unused items. At Hackensack Meridian, for example, kitchen staff load discarded food into containers or onto scales — and then use computer-generated reports to inform future meal-planning efforts.

The Hackensack team has begun slicing more produce in-house — pre-cut veggies spoil faster — and aims to use items like potato peels in recipes instead of tossing them. “We also realized that we could quickly move desserts that never made it onto patient trays into the cafeteria,” he says.

At Wisconsin, a room service model for patient meals trims waste. “Patients can call and order à la carte from a full restaurant-style menu. They might choose a serving of cottage cheese, a salad, and French fries,” says Waltz. “If patients pick what they want, we see less food being wasted.”

Imrie, who also uses the room service model for patients at UVMMC, points to another advantage: Food arrives only when patients are hungry. Adopting the model led to a 20% reduction in food waste within a year, she notes.

But reducing waste is not about consumables alone. Hospitals are also looking to decrease disposable items like plastic utensils that are destined for the dump. UVMMC is preparing to install takeout containers that patrons can return for cleaning and reusing. At UCLA Health, all disposables for patients and customers are compostable or recyclable. Cafeteria staff also offer a discount to customers who bring or buy reusable mugs, and once the health system finishes installing water-filling stations in the next few months, it will no longer sell any single-use plastic water bottles.

“We have hard jobs. We work with flames and knives, but knowing that we are producing food that tastes good, is good for you, and helps protect the environment is great. We can say, ‘I’m proud of what I did today.’”

Lisa Boté

UW Health

Ultimately, though, some kitchen items will continue to get tossed, and leaders are trying to handle waste in the best ways possible.

Composting is popular for its dual benefits: It decreases trash and replenishes soil. “We compost everything,” says Imrie. “If you leave half a sandwich on your cafeteria tray, we compost it. We compost kitchen food scraps. And we compost off the trays that come back from patient rooms.”

At BMC, kitchen staff use a biodigester, a machine that breaks down food easily and quickly. Waste goes in, and a couple of days later emerges as wastewater that gets flushed down the drain. BMC disposes of 2 tons of food trash this way monthly, says Maffeo.

UW Health is also thinking of adding a biodigester, and Waltz thinks her institution will support the purchase if it’s the best long-term choice despite the potential upfront price tag. “There are a lot of leaders here who understand that you can’t necessarily put a dollar amount on what something means for the environment,” she says.

Boté adds that kitchen staff appreciate this orientation. “We have hard jobs. We work with flames and knives, but knowing that we are producing food that tastes good, is good for you, and helps protect the environment is great. We can say, ‘I’m proud of what I did today.’”

Front Nutr. 2023 Apr 17;10:1148137. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1148137. eCollection 2023.

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: Many dietary guidelines promote the substitution of animal proteins with plant-based proteins for health benefits but also to help transitioning toward more sustainable dietary patterns. The aim of this study was to examine the food and nutrient characteristics as well as the overall quality and costs of dietary patterns consistent with lower intakes of animal-based protein foods and with higher intakes of plant-based protein foods among French Canadian adults.

METHODS: Dietary intake data, evaluated with 24 h recalls, from 1,147 French-speaking adults of the PRÉDicteurs Individuels, Sociaux et Environnementaux (PREDISE) study conducted between 2015 and 2017 in Québec were used. Usual dietary intakes and diet costs were estimated with the National Cancer Institute's multivariate method. Consumption of animal- and plant-based protein foods was classified into quarters (Q) and differences in food and nutrient intakes, Healthy Eating Food Index (HEFI)-2019 scores and diet costs across quarters were assessed using linear regression models adjusted for age and sex.

RESULTS: Participants with lower intakes of animal-based protein foods (Q1 vs. Q4) had a higher HEFI-2019 total score (+4.0 pts, 95% CI, 0.9 to 7.1) and lower daily diet costs (-1.9 $CAD, 95% CI, -2.6 to -1.2). Participants with higher intakes of plant-based protein foods (Q4 vs. Q1) had a higher HEFI-2019 total score (+14.6 pts, 95% CI, 12.4 to 16.9) but no difference in daily diet costs (0.0$CAD, 95% CI, -0.7 to 0.7).

DISCUSSION: In a perspective of diet sustainability, results from this study among French-speaking Canadian adults suggest that a shift toward a dietary pattern focused primarily on lower amounts of animal-based protein foods may be associated with a better diet quality at lower costs. On the other hand, transitioning to a dietary pattern focused primarily on higher amounts of plant-based protein foods may further improve the diet quality at no additional cost.

PMID:37139444 | PMC:PMC10150026 | DOI:10.3389/fnut.2023.1148137

Nutr Diet. 2023 Mar 14. doi: 10.1111/1747-0080.12801. Online ahead of print.

ABSTRACT

AIM: To determine the safety, operational feasibility and environmental impact of collecting unopened non-perishable packaged hospital food items for reuse.

METHODS: This pilot study tested packaged foods from an Australian hospital for bacterial species, and compared this to acceptable safe limits. A waste management strategy was trialled (n = 10 days) where non-perishable packaged foods returning to the hospital kitchen were collected off trays, and the time taken to do this and the number and weight of packaged foods collected was measured. Data were extrapolated to estimate the greenhouse gasses produced if they were disposed of in a landfill.

RESULTS: Microbiological testing (n = 66 samples) found bacteria (total colony forming units and five common species) on packaging appeared to be within acceptable limits. It took an average of 5.1 ± 10.1 sec/tray to remove packaged food items from trays returning to the kitchen, and an average of 1768 ± 19 packaged food items were per collected per day, equating to 6613 ± 78 kg/year of waste which would produce 19 tonnes/year of greenhouse gasses in landfill.

CONCLUSIONS: A substantial volume of food items can be collected from trays without significantly disrupting current processes. Collecting and reusing or donating non-perishable packaged food items that are served but not used within hospitals is a potential strategy to divert food waste from landfill. This pilot study provides initial data addressing infection control and feasibility concerns. While food packages in this hospital appear safe, further research with larger samples and testing additional microbial species is recommended.

PMID:36916070 | DOI:10.1111/1747-0080.12801

This event will bring health care, community, Indigenous, government, business, philanthropic, and academic leaders together to explore the power of food in health care to improve patient and planetary health.

Through experiential learning, panel discussions, and hands-on workshops with peers from across the country, participants are invited to share knowledge and learn practices and innovations to improve patient access to fresh, whole foods, reduce food waste and carbon emissions, advance planetary health leadership, and build health equity.

We’ll announce the registration through our newsletter, if you have not already sign up for our mailing list below!

Food has an essential role in our lives, including nourishment and cultural significance, and it also has an impact on local and global economy.

Healthcare institutions are significant providers of food and food services, where meals are offered at least three times a day for staff and patients. They are a perfect point of intervention, in a unique position to offer food as a first step towards nourishment and healing on a patient’s journey.

We 💙 this innovative hospital-NFP partnership whihc has led to recovering hundreds of kgs of food and getting it to the people who need it — while cutting costs and greenhouse gases. Less #FoodWaste ✅ Less GHGs ✅ Better health ✅ Video 👉 youtube.com/watch?v=Zsjymlcm…

Join the Canadian Coalition for Green Health Care, PEACH Health Ontario, CASCADES, and Nourish as we welcome speakers Elísabet H. Brynjarsdóttir and Lindi Close, master’s graduates of UBC, who will present on the integration of plant-rich menus within hospitals and long-term care centres.

We also hear from Marianne Katusin, Director of Support Services at Halton Healthcare, who will speak about the process of integrating plant-based choices into hospital menus and Hayley Lapalme, Co-Executive Director of Nourish, will speak about Nourish’s new Planetary Health Menus climate program to help institutions reduce their food-related emissions.

CCGHC: https://greenhealthcare.ca/

PEACH: https://www.peachhealthontario.com/

CASCADES: https://cascadescanada.ca/

Nourish: https://www.nourishleadership.ca/

Aim: To measure the amount of different types of food and food packaging waste produced in hospital foodservice and estimate the cost associated with its disposal to landfill.

Method: A foodservice waste audit was conducted over 14 days in the kitchens of three hospitals (15 wards, 10 wards, 1 ward) operating a cook-chill or cook-freeze model with food made offsite. The amount (kg) of plate waste, trayline waste and packaging waste (rubbish and recycling) was weighed using scales and the number of spare trays and the food items on them were counted. Waste haulage fees ($AU0.18/kg) and price per spare tray item were used to calculate costs associated with waste.

Results: On average there was 502.1 kg/day of foodservice waste, consisting of 227.7 kg (45%) plate waste, 99.6 kg (20%) trayline waste and 174.8 kg (35%) packaging waste. The median number of spare trays was 171/day, with 224 items/day on them worth $214.10/day. Only 12% (20.4 kg/day) of packaging waste was recycled and the remaining 88% (154.4 kg/day) was sent to landfill along with food waste at two hospitals. Overall 347.3 kg/day was sent to landfill costing $62.51/day on waste haulage fees, amounting to 126.8 tonnes and $22 816.15 annually.

Conclusion: A substantial amount of waste is generated in hospital foodservices, and sending waste to landfill is usual practice. Australia has a target to halve food waste by 2030 and to achieve this hospital foodservices must invest in systems proven to reduce waste, solutions recommended by policy advisors (e.g., waste auditing) and waste diversion strategies.

Keywords: food; food services; health economics; health services; sustainability; waste.

Figure 1

Feedback loops between land degradation,…

Figure 1

Feedback loops between land degradation, climate change, and biodiversity loss. Taken from Figure…

Figure 2

Three streams of decarbonisation for…

Figure 2

Three streams of decarbonisation for reducing life cycle GHG emissions from food waste:…

Figure 3

The plate waste tracker pipeline.

Figure 3

The plate waste tracker pipeline.

Figure 4

Figure 4

A box plot showing the staff cafeteria number of covers (top) and the…

Figure 5

Components of the Prophet model…

Figure 5

Components of the Prophet model used to fit the dining covers in the…

Figure 6

Forecast of the number of…

Figure 6

Forecast of the number of covers on an hourly basis for the period…

Figure 7

The macronutrient forecast on an…

Figure 7

The macronutrient forecast on an hourly basis for the period between April 01…

Figure 8

A sunburst plot showing the…

Figure 8

A sunburst plot showing the carbon footprint (kg CO2eq/kg) of 404 dishes grouped…

Figure 9

Full life cycle assessment of…

Figure 9

Full life cycle assessment of greenhouse gas emissions for different food types: agricultural,…

Figure 10

A prototype of an integrated…

Figure 10

A prototype of an integrated plate waste tracker. It consists of load cells…

Figure 11

Example plate waste detection by…

Figure 11

Example plate waste detection by YOLOv5m model on unseen test plate waste images…

Figure 12

Superposed epoch analysis of 36…

Figure 12

Superposed epoch analysis of 36 weight curves from plate waste disposal. The x-axis…

Figure 13

Clean plate challenge real-time display.…

Figure 13

Clean plate challenge real-time display. It shows a live count of the total…